Written by: Sharon Smith MSc SEBC(Reg) IEng BHSAPC

My niece, Katy Skelton, competed for TeamGB at the London 2012 Olympics, so I witnessed the ‘marginal gains’ approach.

The phrase describes how every aspect of the athlete’s day, beyond training sessions, is examined and optimized to suit individual needs, with a view to maximum performance. A horse may have huge muscles, a strong heart and good bones, but the respiratory system is performance-limiting during intense exercise [1] and it is here where ‘marginal gains’ could really add up.

The phrase describes how every aspect of the athlete’s day, beyond training sessions, is examined and optimized to suit individual needs, with a view to maximum performance. A horse may have huge muscles, a strong heart and good bones, but the respiratory system is performance-limiting during intense exercise [1] and it is here where ‘marginal gains’ could really add up.

Two main factors impact on the amount of oxygen (and carbon dioxide) gases entering (and leaving) the bloodstream [2]:

- How much air gets in and out of the lungs, compared with the blood around the lungs. When air intake volume can’t match the blood flow the result is ‘ventilation:perfusion inequality’.

- The efficiency of gas-exchange across the lung-blood barrier. This can’t happen quickly enough to maintain aerobic muscle function (even in healthy horses) and the result is ‘diffusion limitation’.

When it comes to getting air in and out of the lungs, horses have evolved as obligate nasal breathers, ie. they rarely mouth-breathe. From rest to intensive exercise, air-flow to the horse’s lungs can increase from 5 to 75 liters per second!

Horses can do this because the upper airway (from nose to trachea) has uniquely evolved to widen and become rigid during intensive exercise. Still, the upper airway accounts for 80% of the total air resistance in an exercising healthy horse [3]. This resistance means vacuum pressure in the upper airway increases nearly 20x during inhalation. A mere 20% reduction of the width of the airway in an unhealthy or compromised horse will double airflow resistance. So then, excessively high vacuum pressures deep in the lungs may lead to exercise-induced pulmonary haemorrhage (EIPH) [4].

Horses can do this because the upper airway (from nose to trachea) has uniquely evolved to widen and become rigid during intensive exercise. Still, the upper airway accounts for 80% of the total air resistance in an exercising healthy horse [3]. This resistance means vacuum pressure in the upper airway increases nearly 20x during inhalation. A mere 20% reduction of the width of the airway in an unhealthy or compromised horse will double airflow resistance. So then, excessively high vacuum pressures deep in the lungs may lead to exercise-induced pulmonary haemorrhage (EIPH) [4].

During exercise, airway restriction will be caused by a poorly-fitted or over-tight noseband, over-flexed head and neck (where the rider forcefully holds their horse’s head to the chest), or the horse drawing their tongue back from a harsh bit or tongue-tie pressure. Despite the common practice in racing of tying the tongue to the lower jaw, or out the side of the month, there is no evidence this improves ventilation [5].

Tack and rider aside, microscopic air-born particulates, ammonia from urine, or infection by microbes produce excessive mucus. This promotes BOTH ventilation:perfusion inequality and diffusion limitation during exercise. Nothing beats clean air and grazing, but most horses can’t be kept on pasture year-round. In which case, preserved forage becomes an important consideration. Unfortunately, the process of making, storing and feeding dry hay results in dust [6]. It is now widely accepted that Haygain steamers eliminate harmful bacteria, molds and viruses in hay – and the process considerably reduces respirable dust for the duration of ration consumption.

Tack and rider aside, microscopic air-born particulates, ammonia from urine, or infection by microbes produce excessive mucus. This promotes BOTH ventilation:perfusion inequality and diffusion limitation during exercise. Nothing beats clean air and grazing, but most horses can’t be kept on pasture year-round. In which case, preserved forage becomes an important consideration. Unfortunately, the process of making, storing and feeding dry hay results in dust [6]. It is now widely accepted that Haygain steamers eliminate harmful bacteria, molds and viruses in hay – and the process considerably reduces respirable dust for the duration of ration consumption.

Chronic stress suppresses the immune system [7], so low-stress management keeps the horse physically well. Housing ventilation, hygiene, and dust-free bedding that stays dust-free, are necessary.

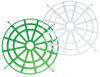

Thoroughbreds were 4x more likely to win races, and 2x more likely to be placed if they had no EIPH or the lowest positive score (Grade 1/4). Yet, over half (≈56%) of the 744 horses in that study were found to be affected by the condition [8]. In a sport where fractions of a second, or a momentary lapse in concentration make the difference between winning and losing, who can afford to ignore marginal gains?

[1] Hinchcliff, K., Geor, R., & Kaneps, A. J. (2008). The horse as an athlete: a physiological overview. Equine exercise physiology: the science of exercise in the athletic horse, 1.1(10).

[2] Dempsey, J. A., & Wagner, P. D. (1999). Exercise-induced arterial hypoxemia. Journal of Applied Physiology, 87(6), 1997-2006.

[3] Robinson, N. E., & Sorenson, P. R. (1978). Pathophysiology of airway obstruction in horses: a review. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 172(3), 299-303.

[4] Poole, D. C., & Erickson, H. H. (2008). Cardiovascular function and oxygen transport: responses to exercise and training. Equine exercise physiology: the science of exercise in the athletic horse. Hinchcliff, KW, 232.

[5] Holcombe, S. J., & Ducharme, N. G. (2008). Upper airway function of normal horses during exercise. Equine Exercise Physiology: The Science of Exercise in the Athletic Horse. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier, 170-192.

[6] Seguin, V., Lemauviel-Lavenant, S., Garon, D., Bouchart, V., Gallard, Y., Blanchet, B., ... & Ourry, A. (2010). Effect of agricultural and environmental factors on the hay characteristics involved in equine respiratory disease. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 135, 206-215.

[7] Elenkov, I. J., Wilder, R. L., Chrousos, G. P., & Vizi, E. S. (2000). The sympathetic nerve—an integrative interface between two supersystems: the brain and the immune system. Pharmacological reviews, 52(4), 595-638.

[8] Hinchcliff, K. W., Jackson, M. A., Morley, P. S., Brown, J. A., Dredge, A. F., O'Callaghan, P. A., ... & Clarke, A. F. (2005). Association between exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage and performance in Thoroughbred racehorses. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 227(5), 768-774.

Image: Distance horses finished behind the winner as a function of EIPH grade. Least square mean (SE). * P < 0.05 vs EIPH 0. Reproduced from Hinchcliffe et al. [8]